How LGDs Interact with Predators

Many producers complain that all their LGD does is bark from early evening through the night and into the early morning. Why do LGDs bark all the time?

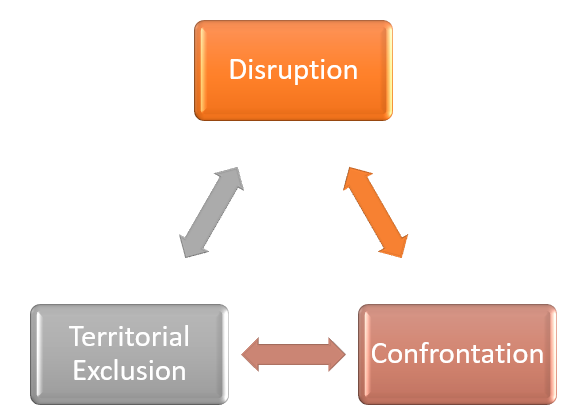

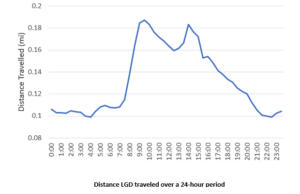

As reviewed last month in the article “Do LGDs Need to be Aggressive?”, LGDs use three different methods that have been bred into them for 1000’s of years to control predation. According to research by Dr. Van Bommel of the Australian National University, LGDs control predators in three ways: territorial exclusion, disruption and confrontation. In research done by Texas A&M University in 2017, it was determined that LGDs travel an average of 7 miles per day over a territory that averages 600  acres (see chart for distance and active times). Territories are areas that are actively defended and are scent marked with feces and urine by the dogs on a regular basis to establish/maintain their boundaries. These scent marks let predators know that another animal is claiming that area. Predators in the dog’s territory are aggressively chased and physically confronted by them. Territorial exclusion has been suggested as the major way that LGDs protect livestock, but recent studies from Australia suggest that disruption of predatory behavior is more important.

acres (see chart for distance and active times). Territories are areas that are actively defended and are scent marked with feces and urine by the dogs on a regular basis to establish/maintain their boundaries. These scent marks let predators know that another animal is claiming that area. Predators in the dog’s territory are aggressively chased and physically confronted by them. Territorial exclusion has been suggested as the major way that LGDs protect livestock, but recent studies from Australia suggest that disruption of predatory behavior is more important.

So why do LGDs bark at night? They are letting predators know that the area is their territory. By barking and using aggressive posturing the dogs are disrupting the predator’s behavior patterns. In the Australian study, LGDs camped amongst the sheep at night and when disturbed, the sheep reacted by flocking together. The dogs barked aggressively and circled the perimeter of the flock. One Maremma left the flock a short distance and challenged the source of the disturbance. The shepherding behavior and aggressive vocalizations of the guardian dogs, combined with the flocking  behavior of sheep, may circumvent the attacks but may not prevent predators from routinely foraging near the sheep. This is why you may still see predators near your livestock. It really depends on our LGDs behavior pattern as to how close they will allow predators to their charges. However, if you are not losing any stock to predation, your LGDs are doing their jobs.

behavior of sheep, may circumvent the attacks but may not prevent predators from routinely foraging near the sheep. This is why you may still see predators near your livestock. It really depends on our LGDs behavior pattern as to how close they will allow predators to their charges. However, if you are not losing any stock to predation, your LGDs are doing their jobs.

The third way LGDs interact with predators is direct confrontation. However, it can happen as seen in the picture. Predators such as coyotes, do not want to have a direct confrontation with a larger canine. Direct confrontations consume a large amount of energy for predators. Attacking a larger canine equates to dominance in canine species, which is why attacks on LGDs are rarely considered unless the coyotes are extremely driven by hunger or some other reason. (Picture courtesy of Tamara Taylor)

LGD Puppy Bonding Project

The pups are all doing great. The Superheroes were neutered on December 17 and are back guarding their livestock. The Stooges are becoming more protective of their charges every week. Moe and Larry often confront the “threats” (usually ASU cows or Texas A&M goats in the next pasture) while Curly will stay with the stock. These three have still not left their pasture for any reason and will not even go through an open gate.

Two of the Superheroes (Hulk & Thor) have left their pasture several times since they have been out of their bonding pens. Once, they were following some of their goats that had gotten through a hole in the fence so I can’t really fault them for that. The rest of the times they have been on adventures to check out perceived “threats” in other pastures. We will see if this continues in the coming weeks. I was alerted to them leaving each time by our GPS tracker system.

I have set up geofences around each pasture that the pups are in and, if they leave, it will send me an email with the dog’s tracker number. A geofence is basically a line that is electronically drawn around each pasture on Digital Matters website of our location. Each pasture has a separate geofence around it. You can adjust the geofence perimeter anytime you want. After you set the trackers, that you want to get an alert from inside each geofence, the system will send you an alert if the tracker leaves that area. Alerts can also be used to let you know an animal entered a location you don’t want them in.

Breed Spotlight – Anatolian Shepard

The Anatolian Shepard is originally from Turkey and can weigh as much as 150lbs. The dogs are from the central region of Anatolia which is a high plateau of endless plains and rolling hills. Summers are dry and brutally hot, and the winters are snowy, with sub-zero temperatures. Anatolian’s descend from some of the oldest known domestic-canine bloodlines, probably from the large hunting dogs existing in Mesopotamia. The breed came to the United States just before World War II when the Department of Agriculture imported a breeding pair for a top-secret sheep dog project to guard part of the nation’s food supply.

Profusely muscled but nimble afoot, Anatolian’s are more than a match for the predators and harsh terrain of their homeland. Anatolian’s are smart, devoted, responsive, and adaptable. They will protect their flock, children and smaller dogs with intensity. They are a large, upstanding, powerfully built livestock guarding dog that is capable of great speed.

The head is broad and strong, and the double coat is dense in cooler climates. It is capable of enduring extremes of heat and cold with a hair coat of 1 to 4 inches in length. The breed is naturally independent, very intelligent and tractable. In manner,  they are proud and confident. They are loyal and affectionate to their owners, but are wary of strangers when mature. They have a powerful neck and well-muscled body that is never fat with strong feet and short nails.

they are proud and confident. They are loyal and affectionate to their owners, but are wary of strangers when mature. They have a powerful neck and well-muscled body that is never fat with strong feet and short nails.

The dogs come in a variety of colors from red fawn to brindle, to blue fawn with a mask, from black to pinto. However, the tan body with black mask are typical of the breed as shown in the picture. Their ears are triangular in shape and rounded as the bottom. Dogs imported from Turkey usually have their ears cropped closely so that they are not damaged in a fight with a predator. The Anatolian is overall a healthy and hardy breed. Hip dysplasia is not common in Anatolian’s, nor is bloat however they can be sensitive to anesthesia. (https://www.ukcdogs.com/anatolian-shepherd and https://www.akc.org/dog-breeds/anatolian-shepherd-dog/)

Hand feeding or self-feeding your LGDs, which is better? Each method has its pros and cons for the dogs and the producers.

Hand feeding LGDs works well for producers that have the time to feed their dogs this way. Hand feeding allows you to monitor feed consumption, easily perform health checks, and allows producers to regularly socialize their dogs. On the other hand, this feeding method is time consuming. The rancher or a ranch hand must go to each pasture at least every other day to feed the dogs. You must also train the dogs to come to a specific location each time to get their feed. Some producers use a whistle or horn to alert their dogs that its time to eat. Hand feeding is even harder to maintain if you have multiple dogs in multiple locations.

Self-feeding your LGDs is a popular choice for many producers with large ranches. Self-feeding allows your LGD to eat when they are hungry. Also, when compared to hand feeding, it is less time consuming if you have multiple dogs and locations. Most self-feeders hold 25-50 pounds of feed which is a benefit for producers with multiple dogs. This amount of feed will usually last about a week in most situations. However, self-feeders are more expensive to purchase than a hand feeding dish and generally require an enclosure of some sort to keep out livestock, hopefully. Also, with self-feeders, producers do not get a chance to regularly socialize their dogs. Cooperators report that well socialized dogs are easier to manage and less likely to travel.

Self-feeders come in a range of prices with and without automation. Each type of feeder has its pros and cons, as well. I will be discussing these systems next month. If you are thinking about self-feeding your LGDs, we recommend that you place your self-feeders near water troughs or bedding areas. This always keeps the dogs with your livestock so that there is a lower chance of predation.

LGD Timely Tips

This month I decided t o only provide one tip and it’s on dog health. One of our dogs, Max, had lost a lot of weight at the end of the summer. Max has been a great guardian of his Angoras at the Read Ranch in Ozona. He never roams and is always with his charges. His biggest fault is that he will not climb into a feeding station. He will only dig under them to get in. We had tried several different things to maintain an appropriate level of nutrition for Max. However, the goats always figured out how to get into his feeding station because Max was constantly digging a hole to get in which also allowed the goats to get into his feeding station!

o only provide one tip and it’s on dog health. One of our dogs, Max, had lost a lot of weight at the end of the summer. Max has been a great guardian of his Angoras at the Read Ranch in Ozona. He never roams and is always with his charges. His biggest fault is that he will not climb into a feeding station. He will only dig under them to get in. We had tried several different things to maintain an appropriate level of nutrition for Max. However, the goats always figured out how to get into his feeding station because Max was constantly digging a hole to get in which also allowed the goats to get into his feeding station!

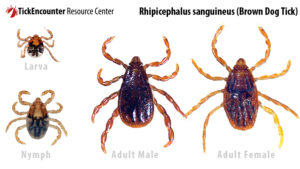

In late September I performed a health check and found Max to be extremely thin. He was brought back to the Center in San Angelo for some rest and to put on some weight. When he got here his stool was very loose, so I administered Forti Flora, a probiotic powder from Purina, to him in his wet feed for a month. It solved that problem and increased his appetite, but he still wasn’t gaining weight. Next, I dewormed him since we were unsure when the last time that had been done. Max was wormed twice three weeks apart, but still nothing drastically changed in his weight. Then I tried a higher quality of feed. I thought that since he was so thin, he may need a better feed to gain weight faster. Again, that only slightly improved his weight and appearance. I decided that Max needed to go to the vets as I was out of ideas. After a simple blood test, our veterinarian determined that Max had a tick borne rickettsial disease called Ehrlichiosis, which is similar to Anaplasmosis in cattle. The disease is commonly spread by the Brown Dog Tick which is found throughout the United States.

Ehrlichiosis occurs throughout the year and can affect several body systems. Dogs can be infected with several strains of this disease and it is prevalent in the lower half of the United States. It attacks most dogs at about 5 years of age. Symptoms include: Lethargy, depression, diarrhea, anorexia, weight loss, fever, head tilt, ocular pain, anemia, respiratory distress and spontaneous bleeding. From initial infection to presentation can be in excess of 2 months.

Once your vet determines Ehrlichiosis is the problem, they will most likely provide you with Doxycycline to administer to your dog for 3-4 weeks. Its important to follow the vets recommended dosage and instructions to remove this disease. Ehrlichiosis can hide and lay dormant in the bone marrow of your dog even after treatment. It’s important to get your dog retested in 9 months after the initial infection to make sure that they test negative for the disease. The best way to treat this disease is to prevent infection by controlling the infestation of ticks on your dog. Proper and diligent use of flea and tick products all year long will keep you LGD happy, healthy and guarding your livestock. (http://tickspotters.org/rhipicephalus-sanguineus-brown-dog-tick) (Blackwell’s Five Minute Veterinary Consult Canine & Feline 6th Ed., ISBN 9781118881309)

To provide feedback on this article or request topics for future articles, please contact me at bill.costanzo@ag.tamu.edu or 325-657-7311.

Bill Costanzo

Research Specialist II, Livestock Guardian Dogs

Follow us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/TAMUlivestockguarddog/