How to Select an LGD Puppy – Part 1

This is the first part of a two-part series on selection of a Livestock Guardian Dog (LGD) puppy. I frequently get questions from producers new to LGDs about how they should select a puppy. Many of them have purchased yearling or older dogs for their first LGD and now want to train their own LGD. I would like to thank all the LGD breeders in our local area, AgriLife Staff and other university staff across the nation for providing input into this valuable project for livestock producers.

An effective LGD is the result of properly rearing a puppy with certain inherent genetic traits. Each farm and ranch should attempt to find the right kind of genetics for their situation. Keep in mind that LGDs behaviors are still greatly influenced by how they are treated during the first year to 18 months of their life. In contrast, physical traits such as hair coat, color, mature size, etc. are preset by genetics.

It’s important to buy LGDs with the genetic predisposition to fit your needs. A knowledgeable breeder will know the parents of the pups being offered and how they worked in the field, as well as their individual personalities and behaviors. Observation over time is generally more reliable than puppy aptitude testing, but a few simple tests and observations can be helpful if you have the hands-on opportunity. It is recommended that you observe the puppies in person before committing to the purchase, yet in some circumstances this is not possible. In this situation, quiz the breeder about traits listed below and request pictures/video of the pups if possible.

A good healthy puppy is critical to the success of your LGD program. Healthy pups are a combination of good genetics and good management. A healthy pup will be the proper weight, with a smooth coat and free of parasites. Be sure to not confuse a potbelly with good health as this may be a sign of improper feeding and/or internal parasites. While these things can be resolved, it will cost you time and money. If a pup you are looking to purchase has more than three defects listed below, you may want to reconsider your choice. Things such as having working parents, being bonded with stock from birth and good health are more important than hair coat length in most areas.

a. Important things to check:

i. Check to see if the eyes are clean and clear, ears are clean, dark pigmented nose, straight forward feet, bright pink gums, straight teeth alignment and a proper gripping bite.

ii. The pup should look wide at the hocks with angulation in the legs and feet pointing forward. This will help to ensure the pup will be able to move correctly as an adult.

iii. What type of hair coat do the parents have? Longer haired dogs in Texas require more maintenance to keep them actively guarding your livestock.

iv. Ectropion eyes (saggy eyelids) are not recommended in LGDs. Check the parents’ eyes. Dogs with saggy eyelids may easily get seeds and other debris caught in their eyelids.

v. How big will the pup grow up to be? Look at parents and siblings. This is a good indicator of the mature size of your pup. Look at feet size; big feet = big dogs. If you have larger predators such as lions or wolves, a bigger dog may be able to better defend against those predators. However, larger dogs require more feed to maintain the size which costs more money. Remember that unusually large pups may suffer from orthopedic problems as adults. It’s always good to check out the parents or siblings from previous litters to determine the adult size of the pups.

vi. Avoid sick, lame or unusually lethargic pups.

vii. Incorrect markings for its breed type may indicate the pup is crossbred with a non LGD. Check out the breed standards online to make sure and ask to see both parents.

viii. Dark pigment on the pup’s lips, nose, and eyelids are preferred. Unpigmented areas can lead to repeated sunburns and could result in early onset cancers.

ix. Ask if the pup is current on vaccinations and a parasite control program.

1. The breeder should provide a list of the products used and dates given.

x. Vet checked – Optional

1. Parents OFA certified (hips)

2. Veterinarian Certified Health Check

A lack of prey drive is critical in an LGD. Prey drive is the instinctive inclination of a carnivore to find, pursue and capture prey. In LGDs, this instinctive drive has been bred against for thousands of years. LGDs have been bred to guard and protect livestock instead. An LGD pup that stalks, chases or bites livestock should be avoided; however, these traits may or may not be exhibited in younger pups. Older pups and yearling dogs should not be exhibiting these behaviors. To test a pup’s prey drive, throw a small object past them. Dogs with low prey drive will often just watch a thrown object go by or investigate it once, but not again. LGDs are not retrievers and should not chase or bring back the object.

LGDs must show a submissive reaction to stock. If you can quietly watch the pups interact with stock, look for a pup that may be curious but is somewhat cautious. Avoiding eye contact with livestock is an excellent indicator of a good instinct. Some LGDs have this instinct naturally and others need to be trained by livestock and/or owners. Livestock guardian dogs need to tolerate pokes and prods by livestock, so you should avoid a pup with a low sensitivity to pain. Avoid pups that bark, jump, or bite stock – even if they are accidentally stepped on. Pups with this behavior can inadvertently injure livestock or cause them to fear the other guardian dogs. Older pups should be submissive and calm around stock. Look for behaviors such as walking up to stock, dropping to the ground or rolling over, lowering the head and tail, licking at the mouths of stock, and choosing to sleep next to stock – even through a fence.

The May edition of the Guardian Way will feature the second half of this article on LGD puppy selection.

LGD Puppy Bonding Project

The Superheroes are all doing well at our research ranch in Ozona. Hulk and Goliath have found out what porcupines are. Goliath had quills in his nose once and Hulk in his back. Hulk is trying to find his place on the ranch he has been traveling back and forth between our Rambouillet’s and our Angoras. The lead dog Duchess has been doing a great job training the pups to be good LGDs.

The Stooges are all doing well at the cooperating producers ranch as well. They have split up into two groups on their own. Larry has his own group of sheep while Moe and Curly are together with a group of sheep. The dogs are staying with their livestock and the producer is happy with their progress.

We have a new group of three pups that are being bonded to groups of Dorper ewes. These pups will be going to our research ranch in Menard after finishing the bonding phase to help our other dogs already at that location. These three pups are the “Legends of Country Music”. Their names are Waylon, Willie and Johnny (L to R in picture). All three pups were donated to the program by a local producer in Lamesa in early March. They are bonding quickly with their stock and already challenging threats to their ewe lambs. The pups are a mix of Great Pyrenees, Akbash and Anatolian Shepard.

Breed Spotlight – Kangal

The Kangal dog is an ancient flock-guarding breed. They look very similar to the Anatolian Shepard but are generally larger in size. The breed is named for the Kangal District of Sivas Province in Central Turkey where it probably originated. Although the breed has long been associated with the family of the Aga of Kangal, most dogs are bred by villagers who take great pride in the dogs’ ability to guard their flocks of sheep and goats from such traditional predators as the wolf, bear, and jackal. The relative isolation of the Sivas-Kangal region has kept the Kangal Dog free of crossbreeding and has resulted in a natural breed of remarkable uniformity in appearance, disposition, and behavior. Despite its regional origin, many Turks consider the Kangal Dog as their national dog. Turkish government and academic institutions operate breeding kennels where Kangal Dogs are bred, and pedigrees are carefully maintained. The Kangal Dog has even appeared on a Turkish postage stamp.

Kangal’s mature slowly even compared to other LGD breeds. The Kangal dog is a large and powerful breed, whose size and proportions have developed naturally as a result of its continued use in Turkey as a guardian against predators. The tail is typically curled. The Kangal dog has a double coat that is moderately short and quite dense. The Kangal dog has a black mask and black velvety ears that contrast with a whole-body color which may range from light dun to gray.

The typical Kangal dog is first and foremost a stock guardian dog and possesses a temperament typical of such dogs-alert, quite territorial, dog aggressive and defensive of the domestic animals to which it has bonded. The Kangal dog has the strength, speed, and courage to intercept and confront threats to the flocks of sheep and goats that it guards. Kangal dogs prefer to intimidate predators but will take a physical stand and even attack if necessary. Kangal dogs have an instinctive wariness of strange dogs but are not typically belligerent toward people. In Turkey they are expected to be gentle with children and tolerant of neighbors.

The Kangal Dog has a short weatherproof coat, neither wavy nor fluffy. In cold weather, the coat is very dense, nearly uniform in length. In warm weather, much of the undercoat is shed, leaving a short, flatter outer coat. The outer coat is harsh, and the undercoat is very soft, dense, and sometimes gray in color. The hair on the tail is never plumed or feathered. The dark hair on the face, head, and ears is quite short.

Color is an important characteristic of the Kangal dog. The true Kangal dog color is always solid and ranges from a light dun or pale, dull gold to a steel gray, depending on the amount of black or gray in the outer guard hairs and in the soft, cashmere-like undercoat. This basic color is set off by a black mask which may completely cover the muzzle and even extend over the top of the head. Their ears are always black. The tip of the tail is usually black and a black spot in the middle of the tail is often present.

Their height at maturity is generally 30 to 32 inches for males and 28 to 30 inches for females. A male Kangal dog in good condition should weigh between 110 – 145 pounds. While a female should weigh between 90 – 120 pounds. We are excited to have two of these dogs donated to our program from a Texas producer to evaluate their effectiveness as a LGDs.

Sources: https://www.kangaldogamerica.com/breed-history-and-standard , https://www.ukcdogs.com/kangal-dog

Dohner, Janet Vorwald. Farm Dogs: A Comprehensive Breed Guide to 93 Guardians, Herders, Terriers, and Other Canine Working Partners. Storey Publishing, 2016.

External Parasites – Fleas

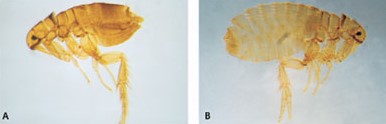

This is the second part of a three-part series on external parasites. It’s advised to treat your LGDs for external parasites year-round. Not only are fleas a nuisance to LGDs, they can spread diseases between host animals and humans. In North America, only a few species of flea’s commonly infest LGDs. Two common species of fleas found on LGDs are the cat flea and the dog flea. However, most of the fleas found on dogs are, cat fleas.

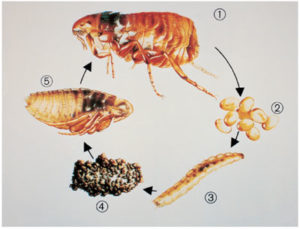

Cat fleas begin reproduction about 1 or 2 days after a blood meal from a host. Female fleas lay eggs as they feed and move about on the surface of the skin. A single female flea can produce up to 50 eggs per day and about 2,000 in her lifetime. The eggs are pearly white, oval, and tiny. They readily fall from the fur and drop onto the soil, where they hatch in 1 to 6 days. Newly hatched flea larvae are mobile and free-living, feeding on organic debris found in their environment and on adult flea droppings. Flea larvae avoid direct light and actively move deep into or under organic debris (grass, branches, leaves, or soil). Cat fleas in any stage of the life cycle cannot survive cold temperatures. They will die if the environmental temperature falls below 37°F for several days. Depending on temperature and humidity, the entire life cycle of the flea can be completed in as little as 12 to 14 days or last up to 350 days. However, under most conditions, fleas complete their life cycle in 3 to 8 weeks.

Flea control measures have changed dramatically in recent years. Flea control previously required repeated application of insecticides on the animal and the premises. Recently, new insecticides and insect growth regulators have been developed that provide residual control and require fewer applications. Insect growth regulators prevent fleas from reproducing by stopping multiple stages of the life cycle. Flea treatments include topically applied liquids, oral and injected medications and fogger sprays.

The goals of flea control are elimination of fleas on dog(s), elimination of existing populations in the environment, and prevention of later infestations of the dog. The first step is to eliminate the existing fleas on the dog. When treating a dog with a product applied to the skin externally, it can take up to 36 hours until the medication has spread sufficiently or reached sufficient concentrations to eliminate all existing fleas. If a more rapid rate of kill is needed, a flea spray or one of the new fast-acting oral products may be desirable. Eliminating fleas in your LGDs environment will be difficult since most dogs are on large properties with livestock year-round. Prevention of infestations is possible with continued application of flea control products.

Many dog owners mistakenly think that flea products either kill all newly acquired fleas within seconds to minutes or completely repel them. Many products do no repel fleas, and long-acting products do not kill most fleas within minutes. Often fleas may live for 6 to 24 hours before being killed. Scrutiny of treated dogs in an infested environment occasionally results in a few flea sightings on dogs for up to 8 weeks and occasionally longer until the infestation is eliminated. You should discuss flea control products with your veterinarian and select one that works well for your dog and the environment in which it lives.

Source: https://www.merckvetmanual.com/dog-owners/skin-disorders-of-dogs/fleas-of-dogs?query=canine%20fleas

http://www.cvbd.org/en/flea-borne-diseases/about-fleas/development-cycle/

Breeder Profile

This month’s LGD breeder and rancher that is effectively using LGDs in their operation is Tamara Taylor of Turkmen Kangal Dogs and Patteran Dairy Goats.

Q: Describe your operation/ranch.

a. How many LGDs do you currently use?

b. Explain your LGD program.

A: My husband and I currently have livestock on only one of our three properties, which makes oversight much easier – for livestock and dogs. We have a small operation with less than a dozen mother cows, about 40 head of hair sheep, and the same of dairy goats. Of course, we have the mandatory flock of free-range hens. The dogs here (Akbash and Kangal Dogs) are exposed to all of these and have cleared coyotes and bobcats, as well as the unwelcome skunks from our acreage.

Q: What got you started in breeding LGDs?

A: In 1980 we lived on a much smaller property. Marauding dogs were doing as much damage to our poultry, domestic rabbits, calves, and even horses as the coyotes were. Our veterinarian told us to look at Turkish dogs, but she specified not Anatolians. At that time Kangal Dogs were a breed known to only a few outside of Turkey. We acquired a registered Akbash Dog and then by 1985 a Turkish friend returned from Turkey with a gift for us – a Kangal Dog, “the famous dog of Turkey” — to go with the Akbash Dog. Within a couple of years, we had several additional imported Kangal Dogs hand-picked for us from villages in the then rather isolated Sivas-Kangal region.

We took on the second breed with the idea of finding out if “lumpers” or “splitters” were correct about Turkish dogs – were they are just one breed (Anatolian Shepherd) or were they different regional breeds like our dairy goats (original from Switzerland but of four distinct breeds) and the neighbors cattle (Galloways vs. Angus, both from the UK).

Q: How long have you bred LGDs?

A: Over time as we have used Kangal Dogs, we have found them to be (typically) quieter, more into “watchful waiting” before they charge an intruder. Unlike the breeds known for “posturing,” barking, and threatening, the Kangal Dog typically stands and watches. Once the decision to go after an intruder is made, the dog is in 150%. To go along with this more “mastiff,” slower to excite disposition, the breed tends to be heavier boned and shorter muzzled than Akbash Dogs, but not as heavy as many Great Pyrenees. Crossbreeding in livestock guarding dogs has muddied the lines so that dogs often have “generic” traits, tending to be more “middle of the road” in behaviors and even appearances. Thus, it can be deceptive trying to decide what a certain breed does when your experience is with crossed dogs. Visual breed ID of most LGDs is simply not possible or accurate.

Q: What breed of LGDs do you raise?

A: Over the years we have used Akbash Dogs along with the Kangal Dogs. In 2013 through 2016, we worked with Dr. Danny Kinka and Dr. Julie Young, who were in the process of importing, getting started, and then studying the effectiveness of three LGD breeds against large predators in the northwest. Grizzly bears and wolves were not deterred by many of the generic white livestock guard dogs found commonly throughout the western states. Karakachans from Bulgaria, Cao do Gado Transmontanos from Portugal, and Kangal Dogs from Turkey were dogs that came to our ranch and were started (and evaluated) with sheep while waiting (up to 10 and 12 months) for cooperating ranchers in MT, WA, OR and UT to take them.

It was an interesting project, and the first that ever used purebred Kangal Dogs in any research project to our knowledge. As a result of that project, we aren’t getting rid of the Kangal Dogs. In fact, an additional 12 from our ranch were added to 20 imports for the program as more dogs were needed on western ranches.

While the project did not come up with recommendations of one breed over another, we did get stories back about a pair of our dogs becoming a deadly pair for predators and absolute coyote killers on their summer range much to the pride of their Chilean herder; however, when that pair (a then 2-year-old neutered male and female) were moved back to the ranch with the sheep for winter, one of their first acts was to attack and lethally maim an older “big white” guard dog. It wasn’t “Aunt Susie’s Golden,” but it was the same ignorance of a working Kangal Dog’s psychology that nearly cost that pair their life at the hands of an angry ranch manager who had never seen the Kangal Dogs before. They were relocated to another ranch, and their Chilean herder-partner was probably disappointed that next summer to find his partners gone.

Kangal Dogs tend to be “homebodies” if they are not allowed to wander as young dogs; they have a short, dense, no-maintenance coat and are bite-inhibited toward livestock and people. If bred to have adequate angulation in the hindquarters, ACL or stifle issues can be avoided. They are powerful and athletic – not as inclined to clear fences at a single bound like some breeds (climbing or digging is still possible!). Develop to be a breed in Turkish villages surrounded by people, other dogs, and livestock all winter means that Akbash and Kangal Dogs would not survive long if they threatened or bit people or livestock in their native land. That culling has taken place before they arrived here! (That said, all young dogs need monitoring particularly with young /vulnerable livestock; a playful young dog may need to be pastured with older muttons or bucks for a while.)

Q: Do you have an LGD mentor?

A: We have learned that being mentored starts with your first dogs from experienced breeders, people who can help you anticipate behaviors, particularly with purebred dogs who have been bred for certain behaviors as well as conformation (and health) traits. Mentoring in the sense of learning more about dogs, their behavior, the relationship between livestock, dogs, predators is an ongoing process. Sharing experiences and information means sometimes we don’t have to make all the mistakes ourselves!

Q: What’s the one thing you wish you knew before starting to breed LGDs?

A: Unfortunately, there has been a lot of confusion about Turkish dogs and specifically Kangal Dogs outside of Turkey. In Turkey, as the rural population decreases and the number of sheep flocks decline (and imports of lamb, a mainstay in the Turkish diet, increase), there has been a rise in crossing dogs once used for livestock protection for Western style dogfighting. Historically livestock protection dogs in many countries bordering and part of the former USSR were “sparred” with each other and even with bears and wolves to help owners evaluate the courage of their dogs. With Turkish purebred native breeds, the Kangal Dog and the Akbash Dog, forbidden to be exported, a variety of crosses and so-called “breeds” are being exported to unwitting buyers.

We were fortunate to have gotten dogs from people who wanted to see them and us succeed. We quickly learned that puppy secure fences are the ONLY way to start pups, just as we were advised. We accepted the fact that Kangal Dogs need separate places to eat and that they will protect their feed from (a reasonable number of) sheep or goats or other dogs! Mentors (in the form of Dr. Jeff Green and Roger Woodruff’s 1990 USDA leaflet) taught us that bonding with livestock took place best in small areas and then continued where young dogs could be monitored.

Q: What is the number one thing you recommend to a new LGD user?

A: Picking the breeder you buy from is as important as selecting the dog or the breed of dog. A good breeder will try to prevent you from getting the wrong dog – some breeds by nature wander, others will act aggressively to people, still others tend to be stray dog friendly, some tend to have stifle/ACL issues, others have coats that mat rather than shed out naturally.

LGD Timely Tips

Every Tuesday check out our Facebook page @TAMUlivestockguardog for Tuesday’s LGD Tip of the Week!

• Never purchase an LGD that is mixed with a non-LGD breed to guard your stock.

• Purchase collars with brass ID tags in case your LGD roams off your property and is found by someone.

• Having an older dog guide a new puppy during its first year on the job is helpful during the training process.

To provide feedback on this article or request topics for future articles, please contact me at bill.costanzo@ag.tamu.edu or 325-657-7311.

Bill Costanzo

Research Specialist II, Livestock Guardian Dogs

Follow us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/TAMUlivestockguarddog/

Follow us on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCF7YbP6bNDV7___6H8mifBA