Home & Work

My boys are finally registered for their college courses after more than two months of delays due to Covid-19 closures and will be starting classes at the end of the month. That was quite an ordeal to go through with limited personal interaction due to the lockdown. Hopefully no one has been too inconvenienced trying to contact personnel at the San Angelo AgriLife Center; we are back working at 50% capacity at our location until further notice.

We are gearing up for the next phase of the puppy bonding project in early fall. We are currently looking for puppies to place into our second trial. Check our Facebook page for the name the puppy contest.

We were happy to have Dr. John Tomecek join us for the July webinar on the LGDs and wildlife. Dr. Tomecek is an Assistant Professor and Extension Wildlife Specialist and was based out of the San Angelo Center a few years ago, but is now based out of Thrall, Texas. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uExmgKerf8A&t=25s

We are now hosting monthly LGD webinars. Each event will be sponsored, and prizes provided by the sponsors may be given away to lucky participants. Each webinar will be on a different topic related to livestock guardian dogs. Check out our Facebook page @TAMUlivestockguarddog for more details and to register for the events. Don’t forget to follow our YouTube channel at https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCF7YbP6bNDV7___6H8mifBA

Internal Parasites – Gastrointestinal

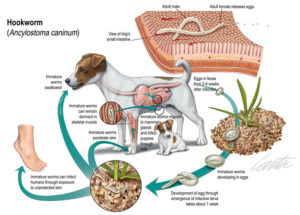

This is the second part of a multi-part series on canine gastrointestinal parasites. The most common type of internal parasites that an owner of LGDs will encounter are worms. There are five main types of worms that your LGD may encounter: roundworms, hookworms, whipworms, tapeworms and flukes. Last month we covered round worms and this month we will focus on hookworms in LGDs.

There are several types of hookworms that can cause disease in dogs. Ancylostoma braziliense infects dogs and is distributed from Florida to North Carolina and along the Gulf Coast in the United States. Uncinaria stenocephala is the principal canine hookworm in cooler regions. It is the primary canine hookworm in the northern fringe of the United States, but it is found with frequency across the country.

Hookworm eggs are first passed in a dog’s feces 15 to 20 days after they are infected. They hatch in 1 to 3 days when deposited on warm, moist soil. Transmission of the worms may result when larvae are ingested or in the case of A. caninum, from the colostrum or milk of infected female dogs. Infections with Ancylostoma species can also result from larval invasion through the skin. Once the skin is penetrated in young pups the worm’s larvae migrate through the blood to the dog’s lungs. The worms are then coughed up and swallowed to mature in the dog’s small intestine. However, in dogs more than 3 months old the larvae may remain in the body tissues in a state of arrested development. These larvae are activated after removal of adult worms from the intestine or during pregnancy. They will then accumulate in the small intestine or mammary glands of the female dog.

A hookworm infection will often cause anemia in young puppies and it may be fatal. The anemia is the result of the bloodsucking and the bleeding internal wounds that occur when these hookworms change their internal feeding sites in the small intestine. This movement of the worms leaves open wounds in the dog’s intestines. An outward sign of infection to look for is pale linings of the dog’s nostrils, lips and ears. Surviving puppies develop some immunity and show less severe signs. Malnourished and weakened animals may continue to grow poorly and suffer from long-term anemia. Mature dogs may harbor a few worms without showing signs. These dogs are often the direct or indirect source of infection for puppies. Watch for diarrhea with dark, tarry feces as this is a sign of severe infections in dogs. Anemia, loss of appetite, weight loss and weakness develop in long term cases of the disease.

There are several drugs and drug combinations that are approved for treatment of hookworm infections in dogs. In addition, many heartworm medications also control certain species of hookworms. Hookworms cannot be seen with the naked eyes. A diagnosis can often be made from the identification of hookworm eggs upon microscopic examination of fresh feces from infected dogs. Your veterinarian can recommend the best treatment for your LGDs if you suspect a hookworm infection.

Sources: https://www.merckvetmanual.com/dog-owners/digestive-disorders-of-dogs/gastrointestinal-parasites-of-dogs?query=canine%20internal%20parasites#v3202812, https://www.petmd.com/dog/conditions/infectious-parasitic/c_multi_ancylostomiasis

LGD Puppy Bonding Project

The Legends of Country Music are now over 6 months old and are all doing well. Waylon’s injuries are all healed up at this point and he is very happy to have rejoined Johnny. Willie had an issue with a front leg. For some reason the growth plate in his knee has fused together already. This in turn caused him to limp which irritated the should and wrist joints. Our veterinarian is not sure why this occurred, as it was only the one growth plate. Willie was prescribed limited movement for three weeks along with an anti-inflammatory medication and a pain medication. He is doing much better now and recently rejoined his brothers. If the problem should return, he will have to be removed from the program as our veterinarian feels he will not be able to effectively carry out his duties on large acreage. We will keep you updated on Willie if the problem reoccurs.

The Superhero’s are all doing well still and getting big! I almost didn’t recognize them the last time I saw them. Thor has wandered twice recently to visit his old friends the Stooges at a cooperating producers ranch. We are trying out a new satellite GPS tracker on the dogs from Optimus Tracking. The trackers are working great and we are getting regular updates on their positions.

These new satellite trackers use 4 AAA batteries and are waterproof. They don’t require cellular service which is a big plus for our ranch location. The company claims that the unit’s batteries should last 6 months so it will be interesting to find out in a real-world application. We will keep you posted how they are working.

LGD Breed Spotlight – Sarplaninac

The Sarplaninac (pronounced shar-pla-nee-natz) is from the mountain region of southeastern Yugoslavia (now Serbia), Macedonia, Kosovo and Albania. This breed was formerly named the Illyrian Shepherd Dog when first recognized in 1939. The name was changed in 1957 to Yugoslavian Shepherd Dog Sharplanina, after the Sharplanina mountain range where the breed is most common. The Sarplaninac is still widely used in its homeland to protect flocks against predators. Until 1970, Sarplaninac’s could not be legally exported from Yugoslavia. Since then, growing numbers of American ranchers have been successfully using Sarplaninac’s for predator control. They prefer more human contact than other breeds which make them slightly less suitable for range operations.

The Sarplaninac is a formidable adversary of predatory animals. This breed has a typical livestock guarding temperament: highly intelligent and independent; devoted to family members and wary of strangers. It is calm and steady but fearless and quick to react to perceived threats. The Sarplaninac is a medium-sized dog who looks bigger than they are because of their heavy bone and thick coats. The length of the dog’s body is slightly longer than its height and the head is in proportion to the size of the body. The Sarplaninac’s ears are drop and V-shaped.

The Sarplaninac is a double-coated breed with a long, straight, rough-textured outer coat and a shorter, much finer and thicker undercoat. The coat on the head, ears, and front side of the legs is short. The hair on the neck, buttocks, tail and the back side of the legs is longer. This variation in coat length results in a ruff at the neck, and frill on the buttocks and backs of the legs.

The dog’s height at maturity is 24 inches or more for males and 22½ inches or more for females. Mature males in good working condition weigh between 77 and 99 pounds. While mature females weigh between 66 and 88 pounds. Despite being slightly smaller than many other livestock guarding breeds, the Sarplaninac is characterized by extraordinary strength. Dogs in North America tend to be slightly larger than their European counterparts. Our producer of the month, Independence Wool, uses these dogs on their livestock operation. Check out what they have to say towards the end of this month’s edition of The Guardian Way!

Sources: Dohner, Janet Vorwald. Farm Dogs: A Comprehensive Breed Guide to 93 Guardians, Herders, Terriers, and Other Canine Working Partners. Storey Publishing, 2016, https://www.ukcdogs.com/sarplaninac

Texas LGD Association

In the fall of 2019 several LGD breeders where contacted by the AgriLife Center in San Angelo in the hopes of establishing an association to support the use of livestock guardian dogs in Texas. The group of local breeders has met several times and have officially formed the Texas Livestock Guardian Dog Association. The goal of the organization is to support, promote and advance the sustainable use of effective livestock guardian dogs by farmers and ranchers. The group of 16 founding members represents a variety of LGD breeders, ranchers and people interested in promoting LGD use in Texas. Bylaws for the association have been created and a temporary board of directors has been selected. The organization is officially recognized by the State of Texas and is in the process of filing a 501c3 nonprofit request with the IRS.

The TLGDA has a Facebook page that can be found @TexasLGDAssociation. One of the main goals is to create a website for breeders to advertise LGDs for sale and to promote the use of the dogs to ranchers. The group will be making a presentation at the AgriLife LGD Field Day in Fredericksburg on September 25. The association is open to anyone that is interested in raising, using or promoting the use of LGDs. Please contact me via email at bill.costanzo@ag.tamu.edu with any questions or how to join the Texas Livestock Guardian Dog Association.

Breeder Profile

This month’s LGD ranchers that is effectively using LGDs in their operation are Dawn and Paul Brown of Independence Wool.

Q: Describe your operation/ranch.

- What type of livestock do you have?

- How many head of stock do your dog’s guard?

- How many acres do your dog’s guard?

A: We are a small sheep and goat ranch located outside of Independence, Texas, between Brenham and College Station. Our home, ranch, and wool mill sit on 80 acres in an area of low rolling hills, live oaks, scattered brush and native prairie grasses. Our range, combined with usual plentiful rainfall, allow for a denser stocking rate which currently consists of 120 Angora goats and fine wool sheep (Rambouillet and Merino). We primarily produce wool and mohair as a source of fiber for the mill, although we purchase raw fiber from other Texas producers as well. We create Texas grown and processed yarn and textiles for the artisan hand-craft market. Our region mostly consists of cattle and horse ranches, and, as it is relatively close to large urban communities, we have mostly part-time weekend-only neighbors. Very little predator control is undertaken in our county, and our biggest issues really surround a hefty coyote population and prevalent town dogs or feral dogs. We do have bobcat, great horned owls, caracara and turkey vultures, but thankfully very few feral hogs. We do have venomous snakes, but mostly copperheads, occasional coral snakes and water moccasins.

Q: How long have you used LGDs?

A: We have had LGDs now for almost 10 years. However, Paul has been a dog person since youth, training, competing, and hunting with Labrador retrievers. Growing up, I was always surrounded by dogs and, as a youth, I participated in conformation dog shows with 13-inch beagles. Sporting and hound dogs are very different than the LGD, but you certainly learn a lot about drive, instinct and training from those breeds. With my beagles, they were easily trained and groomed for the show ring, but after you cleaned them all up, if you happened to walk them on the leash past a certain smell, they would drop and roll in it every time!

Q: How many dogs do you use?

A: We usually have four dogs- two with the wethers/bucks, and two with the does/ewes and their kids/lambs. We have two GP females, and one Sarplaninac male. This June we lost our six-year-old Sarplaninac female to Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia. We are fortunate that all the dogs got along very well, three were spayed females, and one is an intact male. The groups of two dogs always shared a fence line with each other, could easily switch partners, and all four worked together in the same pasture if need be. Our two female GPs are litter mates and came to our ranch at 10 weeks of age. They came from working parents and were raised with our goats. Raising sibling females is

controversial in the LGD world, but it worked great for us. They are matched in energy, independence, guarding style, stock bonding, and lack food/resource aggression… most of all, no fighting between themselves or the other two dogs. They are now 9 years old, and still work together. We were told via the online LGD forums that we “just got lucky” … perhaps… but I believe there is a missing “link” to this issue. Our Sarplaninac’s were imported from Canada, from Grazerie Ranch, Louise Liebenberg. We were looking for a steadfast, loyal guardian with a harder edge in dealing with the coyote load in Texas. Our male dog was 3 years old when imported, and the female was 11 weeks of age. These two dogs shared the same sire, so they were not to be a breeding pair. We spayed the female and left the adult male intact. These dogs are not common in North America, and we thought a litter sired by him could be possible one day down the road.

Q: Do you prefer a specific breed of LGD?

A: I wouldn’t say one breed is preferred over the other, but what we needed were dogs that could be trusted to guard and be companionable as well. As a small ranch and producer, our stock is handled or managed daily in a manner more intensively than a large thousand-plus acre operation. We spend a lot of time around the livestock and dogs, so we sought breeds and breeders that bonded well to their shepherd and flock/herd. I would say our GPs are fairly typical. They bark and posture at threats, move goats off the fence line when they sense danger, putting themselves between the goats and whatever has caused the alarm. They tend to stay in amongst the sheep and goats. They are less aloof than the Sarplaninac and enjoy a great deal more head petting. Overall, the Sars are a harder dog. They are “guardy” and can be a whole lot of dog for one to handle. It is a primitive breed, very old, if not one of the oldest LGD breeds. Having said that, our older male dog, Shadow, is friendly, polite with strangers, incredibly stable and calm, but always on the watch. He was raised in Canada with sheep and seems to prefer their company. Our female Sars that we lost in June was always a handful. She was the most vigilant and reactive of the dogs and would go right through or shimmy under a fence to get at a threat. She was always on the higher-energy side. She required a yoke when in the pasture most all her life. We stopped her as an adolescent from pulling Angora goats around by the tail and dealt with her food aggression. She went on to never hassle or injure stock. She was the best at coming to you when her name was called, and she never picked fights with the other dogs- after she grew out of continuously ankle-biting them as a puppy. It wasn’t always sunshine and roses with her, but she was a good dog and we learned a great deal. Both breeds of our dogs have a denser coat that requires extra care. The Sars have a correct working coat, and thankfully due to our milder winters produce less of a downy undercoat. We do have to manage for spear grass in our area, and feel it is best to clip the belly and leg hair for the dogs. We also clip the hair under their ears in the summer as it seems to help them stay cool and have fewer ear ailments.

Q: Do you have an LGD mentor?

A: Someone I have enjoyed following over the years is Louise Liebenberg of Predator Friendly Ranching Blog, High Prairie, Alberta. We imported our two Sarplaninac’s from her in 2014. While her range is vastly different than ours, I felt that her methods were generally based on the idea that by making management decisions that set your dog’s up for success, many problems can be avoided and therefore the rancher, dogs, wildlife and livestock all benefit. This goes for just about everything, deciding how the dogs are fed to reduce the chances of food aggression, what fencing type and height to decrease roaming, GPS and identifying collars for location if dogs wander, socialization and basic obedience training to promote a safe “good citizen” guardian at the ranch or if in contact with the public. Louise also implements nighttime corralling with her stock and dogs, and that is something that works well for us, too. Our sheep and goats, along with the dogs, come back to shelter in the evenings. This paddock is enclosed behind a gate overnight. In the morning, chores are finished, and everyone is turned back out to their pastures.

Q: What’s the one thing you wish you knew before starting to use LGDs?

A: I would have to say when doing research regarding LGDs and their management, be wary of individuals that offer knowledge or advice in absolutes. Language such as “must always”, “don’t ever”, and “must not” when dealing with working dogs doesn’t agree with me. The varied range conditions, operations sizes, type of stock guarded, and breed characteristics, make it hard for a “one size fits all” absolute approach. Starting down that path early into LGDs can set you up for disappointment and discourage you from finding what really works for your ranch.

Q: What is the biggest thing you recommend to a new LGD user?

A: Consider treating the dogs like the valuable asset to your ranch that they really are. Treat them well and set them up for success. Give

them fewer obstacles to an already tough job. Provide them good food, clean water, quality vet care, correct fences. Give them a way to get back to you if they get lost chasing a predator- microchip, GPS collar, collar with tags. Depending on your area- let your neighbors know what to expect from your dogs, educate them about the dog’s job and value to livestock and wildlife. Reinforce the dog’s good behavior, have positive energy, smile and be kind. If you feel like throwing things, screaming, and punching a wall, and that can happen with LGDs, try not to scream and throw things at them. If something goes wrong, take a step back, see if you had a role in the outcome before claiming the dog failed. No one is perfect, no dog is perfect, but a good LGD is worth all the effort.

Q: What is your favorite LGD or LGD story and why?

A: Paul’s favorite story: Angora goats, and goats in general, can easily get themselves into predicaments. One evening in early fall, one of our yearling bucks in full fleece found himself stuck in bramble vines and unable to get free. When the herd headed off to the barn before dark, he was left behind and struggling to get free. One thing that is handy when nighttime corralling our animals, is that you notice when all the dogs are not back at the barn at dusk, sometimes that is easier than counting all the goats. And on this night, one of the GPs didn’t return with her goats. Paul went out to search for her and found the buck in the brambles with the dog standing by. Good dog.

Dawn’s favorite story: My story has to do with an unexpected visitor in the barn. When we first started raising Angora goats in 2010, my job had taken us from Texas to Northeast Arkansas. I was practicing rural women’s health out in the foothills of the Ozarks, near the Missouri border. In addition to the goats, we also raised black Angus seedstock via AI. One afternoon during a torrential rainstorm, I was working in the office area of the barn and had the dogs inside with me. Our goats were like indoor cats and never liked to be wet, so they were bedded down undercover during the storm. The rain was so heavy on the metal roof that I didn’t hear anyone approaching barn, but when the door opened and a hooded raincoat clad man entered with the liquid nitrogen for the cryo tank- the dogs were up and barking angrily- I call it the vicious “police dog” bark. He backed out fast!

LGD Timely Tips

Every Tuesday check out our Facebook page @TAMUlivestockguardog for Tuesday’s LGD Tip of the Week!

- Ticks don’t engorge within 24 hours. If you see an engorged tick it means it has been there for longer. The feeding period can range

Engorged Brown Dog Tick & normal Brown Dog Tick from several days to more than a week.

- The brown dog tick is the perfect vector for several dangerous pathogens including Ehrlichia canis and Babesia vogeli.

- Heartworm microfilariae can be transmitted to unborn puppies via the placenta. So,

Heart Worm Microfilariae puppies may be born with microfilariae in their circulatory system!

To provide feedback on this article or request topics for future articles, please contact me at bill.costanzo@ag.tamu.edu or 325-657-7311.

Bill Costanzo

Research Specialist II, Livestock Guardian Dogs

Follow us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/TAMUlivestockguarddog/

Follow us on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCF7YbP6bNDV7___6H8mifBA