AgriLife LGD Program Update

By: Bill Costanzo, Texas A&M AgriLife Research

Spring is here and flowers are blooming in the pastures. It’s almost time for the second round of puppies in the bonding project to leave the Center and move on to our research ranches and a cooperating producer’s ranch. Hopefully you had a chance to check out Dr. Zoran’s very informative webinar on LGD nutrition on March 25. If you missed the live event, you can view it on our YouTube channel Texas A&M AgriLife Livestock Guardian Dog Program – YouTube. Our next webinar will be held on May 20 at 3pm. That webinar will discuss legal issues facing producers using LGDs. You can register for the event on our Facebook page or on the AgriLife Centers website under the events section.

This month we will start a three-part series on internal parasites presented by our guest writer. Dr. Meriam Saleh, Ph.D., from the Texas A&M Department of Veterinary Pathobiology at the College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. Dr. Saleh recently moved from Oklahoma State University and has be a guest presenter twice for the AgriLife LGD Programs bimonthly webinars.

Guest Article: Common intestinal parasites of livestock guardian dogs, part 1 of 3

Dogs, including livestock guardian dogs, can become infected with a variety of parasites. Most people are familiar with ticks and fleas, which are types of ectoparasites (meaning external parasites) that we can see on the skin of our dogs (and sometimes even people), but people are less familiar with endoparasites (meaning living inside the host) of dogs. The most common endoparasites infecting dogs include hookworms, roundworms, and whipworms. Dogs become infected with these parasites a few different ways, but a common theme among all three of these worms is that once infected the dog’s environment also becomes contaminated by the parasite which can lead to greater infections or reinfection after treatment, which is why it is important to treat parasitic infections in a timely fashion and in consultation with your veterinarian. The best parasite treatment is actually prevention, and the Companion Animal Parasite Council recommends that every dog be administered year-round broad-spectrum parasite control that is effective against heartworm, intestinal parasites, fleas, and ticks—with particular attention to controlling parasites that are zoonotic, meaning they infect people too.

Hookworms, roundworms, and whipworms fall into the category of intestinal parasites and there are a variety of routine preventive products available to treat and control these infections. Ask your veterinarian what they recommend; there is not one best parasite control product as it depends on your dog’s history, lifestyle, and the type of product you want to administer plus a variety of other factors. It is also very important that pregnant and nursing dams are maintained on broad-spectrum parasite control products as some parasites can pass to the puppies in utero or when the puppies nurse. It is better for the health of the puppies to prevent infections from ever occurring whenever possible.

I mentioned earlier that hookworms, roundworms, and whipworms can all contaminate the environment of an infected dog creating potential for reinfection or an even greater worm burden for the already infected dog. Let’s take a closer look at how dogs acquire these parasites. In this first post, we will look at hookworms.

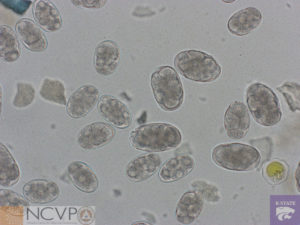

Hookworms live in the small intestine of the dog, where they attach to the intestinal lining and suck blood from the host (Image 1). Hookworms are voracious blood feeders and can cause significant anemia and even death in severely affected puppies. Hookworm infections may also cause diarrhea and some weight loss. In addition to feeding on blood hookworms’ mate and lay eggs in the small intestine. Hookworm females shed a large number of eggs every single day—these eggs are then passed in the feces when the dog defecates (Image 2). Once in the environment the eggs will begin to develop forming a larva inside, eventually the larva will hatch out of the egg and further develop until it reaches the third stage, which we call an L3. This L3 then infects a host (either the same or another dog, or sometimes people depending on the exact species, more on that later)

when it is ingested or when it penetrates the skin.

After the L3 is either ingested or penetrates the skin of the dog it will migrate in the tissue to arrive in the small intestine. Some of the migrating worms may stay in the tissue and become arrested, which means they pause their development, while the rest go on to the small intestine and become adults that suck blood, mate, and lay eggs. These arrested larval worms can reactive or resume their development and go on to the small intestine at a later time, or in the case of a pregnant dam may reactive and move to the mammary tissue to infect nursing puppies via the milk. These worms make their way to the small intestine of the puppies and the life cycle repeats itself.

I mentioned earlier that sometimes that infective L3 stage in the environment can infect people too. Again, it depends on the specific hookworm species, but Ancylostoma braziliense, which occurs in warm coastal areas of the United States as well as Central and South America, and Ancylostoma caninum, which is the most common hookworm of dogs in the United States both can and do infect people. The L3 stage can penetrate the skin of people too and can use something called cutaneous larva migrans (CLM), which is when the larvae migrate in the skin and cause red winding tracks that are very itchy. Most cases of CLM are diagnosed in the southeastern and Gulf Coast areas of the United States. An easy way to avoid larval penetration of the skin is to be sure to wear shoes. CLM is easily treatable but does cause mild discomfort when infected.

You can see how quickly an infection can lead to a contaminated environment and even more infective parasite stages to keep the infection going, which is why routine use of preventive products is so important, particularly for a zoonotic parasite like hookworm. For more information on these and other parasites you can check out the Companion Animal Parasite Council and their Pets and Parasites website (https://www.petsandparasites.org). In the next post we will talk about the roundworms and last whipworms.

Written by: Meriam N. Saleh, Ph.D., is a Post-Doctoral Research Associate at the Texas A&M Department of Veterinary Pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences. Dr. Saleh currently serves as the project leader for the National Center for Veterinary Parasitology. In 2019 she completed a two-year postdoctoral fellowship focused on ticks, their geographic disruption, and tick-borne diseases at Oklahoma State University. She earned a BS in Animal Science from the University of Tennessee in 2011 and a Ph.D. in Veterinary Parasitology from Virginia Tech in 2017. She is also an active member of the American Association of Veterinary Parasitologists.

LGD Puppy Bonding Project

Several of the puppies discovered our resident porcupine last month. Lenny, Laverne, Squiggy and Louise have all had quills in them as of the end of March. Laverne ended up going to the vet for a couple that we were unable to remove at the Center. Hopefully the other three pups don’t find out about the porcupine. The current round of puppies will be getting spayed and neutered this month. They are all 8-9 months old and will be leaving the Center for our ranches and a cooperating producer’s ranch in May. It’s important to get your LGDs spayed or neutered before their first heat cycle to decrease the chances they may roam looking for a mate.

The puppies bonded in hot wire pens (Laverne, Lenny, Squiggy and Wyatt) are staying in their pasture. Laverne and Lenny left once due to a large hole in the fence but have not wandered out of the pasture again once it was fixed. The other three pups (Doc, Thelma and Louise), as seen in the picture above, bonded without hot wire have been leaving their pasture on a regular basis. Doc and Louise have left it a few times to check out the nannies and new kids in the pasture next to them. Thelma, however, has been leaving almost daily from her pasture to visit LGD Thor, the nannies and kids. We placed Thelma in the kennel for a few days as punishment to see if it would change her behavior.

Thor has been roaming much less since he has been at the Center. He has not left his pasture since late February. The nannies Thor is

guarding are all kidding at this point, so he is staying pretty close to them now. Thor even refused to leave the area of a dead kid for 2 days until we finally found it and took it away. He seems to be doing well now that he is with a couple hundred meat goats. Sometimes you need to keep moving a dog until it finds the type of animals its comfortable guarding. Thor and his siblings stayed closer to the goats they were bonded with than the sheep when they were released from the bonding pens.

We had some issues with Waylon playing rough with young lambs last month. We placed a drag on him for a few days and then released him again. He was still playing with them, so we decided to move him to a set of older ewe lambs and dry older ewes until he gets older and calms down. Waylon is very playful still at 13 months of age. Most LGDs don’t mature until at least 18 months of age. Waylon has several more months to go before we can give him more responsibilities and completely trust him on his own with livestock. He rarely follows the feed truck now so hopefully we have moved past that issue with him. He is still very friendly and easily caught in the field anytime I need to catch him.

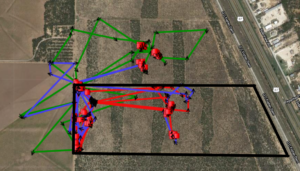

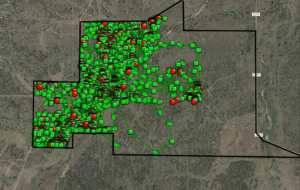

Johnny has been doing well at our ranch in Menard. It appears that separating the brothers in November of 2020 was a good idea. He has not roamed off the ranch property since the separation. Below is a picture of Johnny’s travels for 1 month. He is staying predominately with the Dorper sheep which is what he was bonded with. He has been seen with our meat goats at times, but it looks like he is guarding the livestock we need him to guard. The sheep are staying on the West side of the ranch which is where Johnny is spending most of his time based on the GPS tracking data. Most of the ranch is open due to a multiyear research project so the livestock and LGDs can move to any location they want on the 4000 acres.

If you enjoyed my monthly blog, don’t forget to subscribe to it The Guardian Way | Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center at San Angelo (tamu.edu). To provide feedback on this article or request topics for future articles, please contact me at bill.costanzo@ag.tamu.edu or 325-657-7311. The Texas A&M AgriLife Livestock Guardian Dog Program is a cooperative effort by Texas A&M AgriLife Research and the Texas Sheep and Goat Predator Management Board. Make sure to follow us on our social media sites and share them with your friends and family!

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/TAMUlivestockguarddog/

Instagram: @tamulivestockguarddog

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCF7YbP6bNDV7___6H8mifBA

Don’t forget to check out the Texas LGD Association on Facebook! Follow the organization at https://www.facebook.com/TexasLGDAssociation